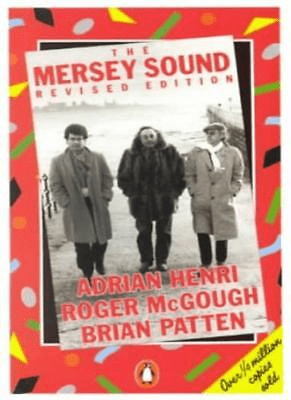

When the collection The Mersey Sound appeared in 1967, British poetry abruptly lost its academic sheen – and suddenly came alive. Three young poets from Liverpool – Roger McGough, Adrian Henri, and Brian Patten – proved that poems could be heartfelt, streetwise, and free of metaphysics. Patten, the youngest of the trio, grew up on the border of poetry and journalism, public life and inner silence. He left behind a style that continues to inspire, alongside names like Carol Ann Duffy. In this article on iliverpool.info, we discuss how Patten grew up, his cultural contribution, and how one of Brian’s poems became a way to say goodbye to those we have lost.

From the Streets of Bootle to the First Poems

Brian Patten was born on 7 February 1946 in Bootle – a working-class district near Liverpool. This area formed the backdrop of his poetry: the industrial landscape, a childhood amidst brick and smoke, and a feeling of loss and longing that poured out into the lines of the adult poet. Brian left school early – not because of laziness or rebellion, but because life demanded action: by 15, he was already working as a journalist for the local newspaper Bootle Times, where he ran a music column. This was his new creative experience – reporting, not poetry.

Patten recalled that during that period, poetry appeared in his life before literary studies. He wrote what he wanted to say, not what “ought to be a poem.” And this became the foundation of his later poetics: to be genuine, not to overcomplicate, and to trust his own voice.

At 18, Patten travelled to Paris – not for a bohemian image, but to live, perform, and sometimes write poems in chalk on the pavements. This image – a young poet leaving lines on the cobblestones – too accurately illustrates his early creative credo: poetry should be accessible, physical, alive, and close to people.

Against this backdrop, his first performances in Liverpool – even before publications – looked more like musical improvisations than poetry evenings. He stood before the audience not as a “young man of letters,” but as a person who had something to say. And the audience – usually young, sometimes accidental – heard it.

This was the start of a career that redefined what modern poetry could be: free from the tinsel of academia, with the smell of dock smoke in its hair, and a voice unashamed to speak plainly.

The “Liverpool Poets” and The Mersey Sound Revolution

In the mid-1960s, Britain’s poetic life had a distinct dual reality: on one side, prestigious journals, Oxford academics, and high style; on the other, clubs, basements, and stages where poems were read with guitars, with laughter, and without complex metaphors. It was in this second environment that the phenomenon soon to shake the entire poetic community was born – the Liverpool Poets. And one of the main voices of this wave was Brian Patten.

In 1967, he published the anthology The Mersey Sound with Roger McGough and Adrian Henri. The title was a direct nod to the popular wave of Liverpool music at the time (The Beatles, Gerry & the Pacemakers), but the content was poetic, though no less rhythmic. The anthology instantly became a phenomenon: it was bought up not by literary critics, but by students, shop assistants, and nurses. A true poetry bestseller.

What was the secret? First, accessibility: the authors were not afraid of colloquial language, irony, or everyday topics. Second, sincerity: these poems expressed genuine feelings – infatuation, boredom, anger, tenderness. Third, public visibility: the poems were created not for the shelf, but for the stage, for live contact with the audience. And Patten was arguably the most melancholy, the most serious of the trio – his texts often delved into themes of memory, loss, and childhood experiences.

The Mersey Sound was, and remains, a rare example of poetry becoming a truly mass phenomenon. The collection sold hundreds of thousands of copies, influenced entire generations of young poets, and proved: a poem doesn’t have to be complicated to be considered profound.

And although critics did not immediately take the “Liverpudlians” seriously – calling them too lightweight, too popular – time put everything in its place. They changed the poetic landscape. And Patten, with his gentle view of simple things, became one of the most expressive voices of this change.

So Many Different Lengths of Time: The Poetics of Memory

In Brian Patten’s later work, there is a clear gravitation towards the theme of loss – not showy, but internal and personal. One of the most moving embodiments of this was the poem So Many Different Lengths of Time. Written after the death of his friend, the artist and poet Adrian Henri, the text became a kind of ritual of remembrance that is quoted at funerals, in obituaries, and on parting pages.

And this is precisely why it is worth dwelling on it separately – as a poem that united the human and the poetic, the personal and the universal.

The Poem as an Emotional Ritual

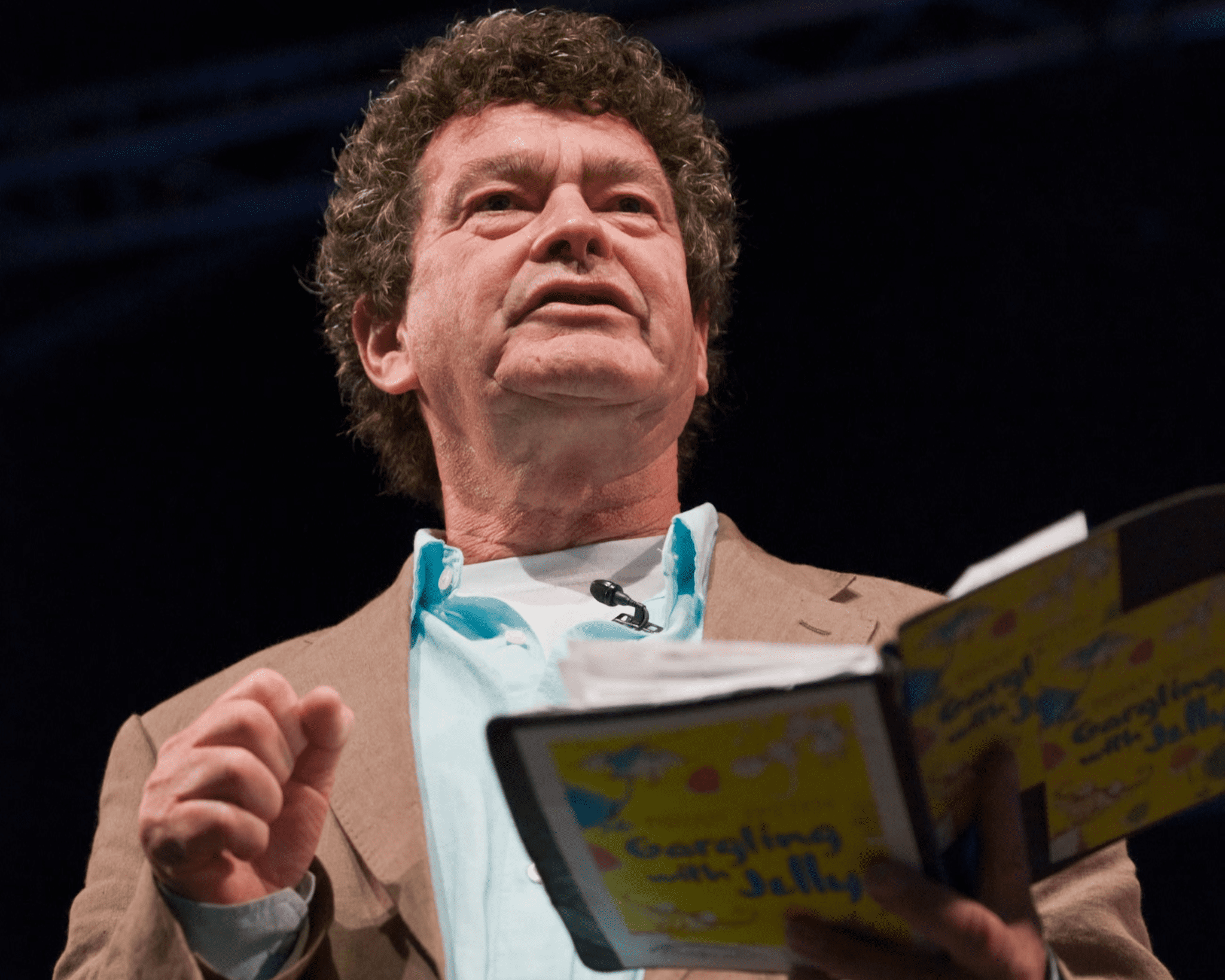

So Many Different Lengths of Time has become an almost canonical text for farewells. It is read not only by close friends who have passed away but also by actors at public ceremonies: notably, during Ken Dodd’s memorial service in Liverpool, the poem was read before thousands of people. Patten himself also read it at Henri’s grave – with a tremor in his voice, without unnecessary theatricality.

All this suggests that the text entered living culture; it is not merely read – it is used when people lack their own words. In this sense, the poem acquires the power of a prayer – although Patten himself never wrote in a religious spirit.

Theme, Imagery, and Intonation

The poem begins with the question: “How long does a person live?” And the answer is not biological, but follows a poetic logic: a person lives as long as the memory of them lasts in the hearts of others. Someone for a day, someone for years, and someone “as long as love exists.” The imagery is simple: scents, voices, smiles that we carry with us.

The poem’s intonation is quiet, gentle, and without pathos. Patten does not moralise or save from pain – he is rather simply present. Like a friend who explains nothing but is there in the moment of silence.

The Poetry of Maturity

This poem is difficult to imagine in the period of The Mersey Sound. That era held youth, irony, and quick rhymes. Here – silence, slowing down, and the honest acceptance of pain. This is the voice of Patten, who has passed through loss, maturation, and re-evaluation. In Armada and other later collections, he increasingly addresses the themes of childhood, the death of his mother, and solitude – but not with despair, but with dignity.

So Many Different Lengths of Time is a text, in part, about memory also being a form of love. And Patten left behind words that people remember and quote in the most difficult moments.

Recognition, Death, and the Voice Still Alive

Brian Patten’s style was to talk about the complex without glamour, without an academic tone, without poetic adornment. To understand and love his texts, one did not need a literature degree – it was enough to have a heart. And it was for this that the Liverpool poet was recognised – both in artistic circles and by the public.

In 2003, the Liverpool poet became a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. Even earlier, in 2001, he received the Freedom of the City of Liverpool alongside McGough and Henri. Brian was awarded literary prizes, read at festivals, and quoted at ceremonies – and at the same time, his poems remained on the shelves in ordinary homes, in school anthologies, and on postcards.

He was a poet who was genuinely read. Significantly, after the news of his death on 29 September 2025, the internet was filled with questions like, “Is Brian Patten still alive?” This means that, however cliché it may sound, given the Liverpudlian’s most famous poem described above, he still lives in people’s minds – like a voice in headphones, like the storyteller of countless interesting tales from a book you reread.

This, perhaps, is the main point: Patten was not a “poet of life” or a “poet of death.” He was a poet about people and for people – with all their weaknesses, tenderness, and fears. And this simple, yet profound, poetry truly doesn’t age.