In the early 1900s, an institution far ahead of its time emerged in Liverpool. The Johnston Laboratories became a catalyst for the development of biomedicine in Great Britain. This was a place where discoveries were born that would influence the course of medicine – from the fight against tuberculosis to the study of vitamins and tropical diseases. Why is this story still important today, and what remains of it on the map of Liverpool? Read on at iliverpool.info for an insightful and slightly unexpected journey.

The Beginning: Philanthropy Meets Science

The early 20th century was a period when medicine was just beginning to establish itself as a systematic science. Cures were often developed by trial and error, infectious diseases decimated entire cities, and laboratory research was a privilege reserved for a select few. It was in this environment that a groundbreaking idea was born: to create an independent centre where scientists could study the nature of diseases and search for ways to overcome them.

The funding for the laboratories was provided by William Johnston, a local philanthropist who believed in the power of science. His charitable contribution made it possible to establish the first professorship of biochemistry in Great Britain. This was a true breakthrough, as the science of chemical processes in living organisms had neither established methods nor widespread support in academic circles at the time.

The university itself actively supported the initiative. The Johnston Laboratories were organically integrated into the structure of the Faculty of Medicine and immediately began to collaborate with other scientific institutions, including the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, which was also based in the city. This is where an environment was formed where philanthropy, academic freedom, and scientific passion came together in one place.

At the Forefront of Science: Research Directions

Even before the word “interdisciplinary” came into fashion, the Johnston Laboratories were already practicing it to the fullest. They were not limited by the framework of a single speciality – here, they conducted parallel research into biochemistry, oncology, tropical infections, parasitology, and even comparative pathology (a field that compares diseases in humans and animals). Such a diversity of topics allowed them to turn knowledge into practical medical tools.

One of the most important areas of research was tropical medicine. At that time, Great Britain had numerous colonies in Africa and Asia, so the study of malaria, yellow fever, and schistosomiasis was not only a scientific but also a political task. Part of the laboratory facilities were temporarily allocated for the needs of the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, which later gained global recognition.

The research results did not remain in a desk drawer. They were published in a dedicated journal, the Thompson Yates and Johnston Laboratories Report. This was a kind of scientific diary that recorded discoveries, methodologies, pathology analyses, and the first attempts at treatment. Thanks to this report, information spread among universities and clinics, fuelling the development of medicine throughout the country.

The Johnston Laboratories became an example of how a small structure within a university can work as an autonomous scientific engine – flexible, bold, and open to collaboration.

Distinguished Names and Major Discoveries

The history of the Johnston Laboratories should not be reduced to just its walls and equipment. Above all, it was created by the people who worked there. Their names are not household names today, but without them, there would be neither modern biochemistry nor a whole host of medical breakthroughs.

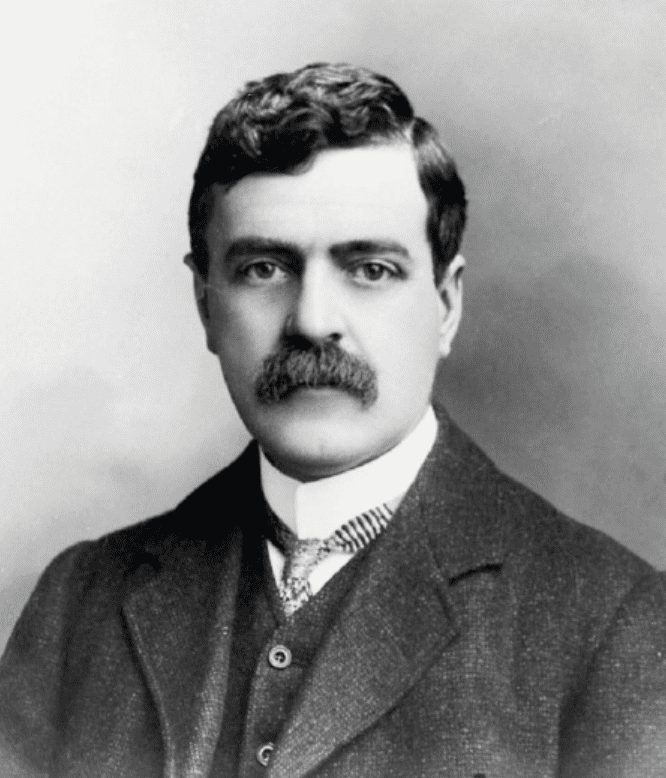

Among the first scientific directors of the laboratories was Benjamin Moore, the first person to hold the newly established Johnston Chair of Biochemistry. He was not interested in repeating others’ experiments: he strived to create a new science. It was Moore who founded The Biochemical Journal in 1906, one of the most authoritative scientific publications in the world of biochemistry, which still exists today. In his research, he focused on tuberculosis – a deadly disease at the time – and brought closer an understanding of how the body fights mycobacteria.

Subsequent generations continued this legacy. Richard Alan Morton, who headed the Department of Biochemistry from 1944 to 1966, stands out. His laboratory was the first in Great Britain to use spectroscopy to study biomolecules – that is, to analyse how substances absorb and emit light to understand their structure. This made it possible to identify vitamin A₂, ubiquinone (coenzyme Q₁₀), and polyprenols – compounds that are still used in dietetics and pharmaceuticals.

Such discoveries were made possible by the relative freedom that the structure of the Johnston Laboratories provided. There was no rigid hierarchical control, and scientists could focus on what was truly important: the study of the complex, unpredictable, and fascinating nature of life.

What Remains: Buildings, Ideas, and Influence

Over time, science branched out, and new fields and specialities emerged – and the Johnston Laboratories gradually changed their role in this process. Some premises were rebuilt, and others were given to different departments. But although the sign disappeared, its spirit remained within the University of Liverpool itself.

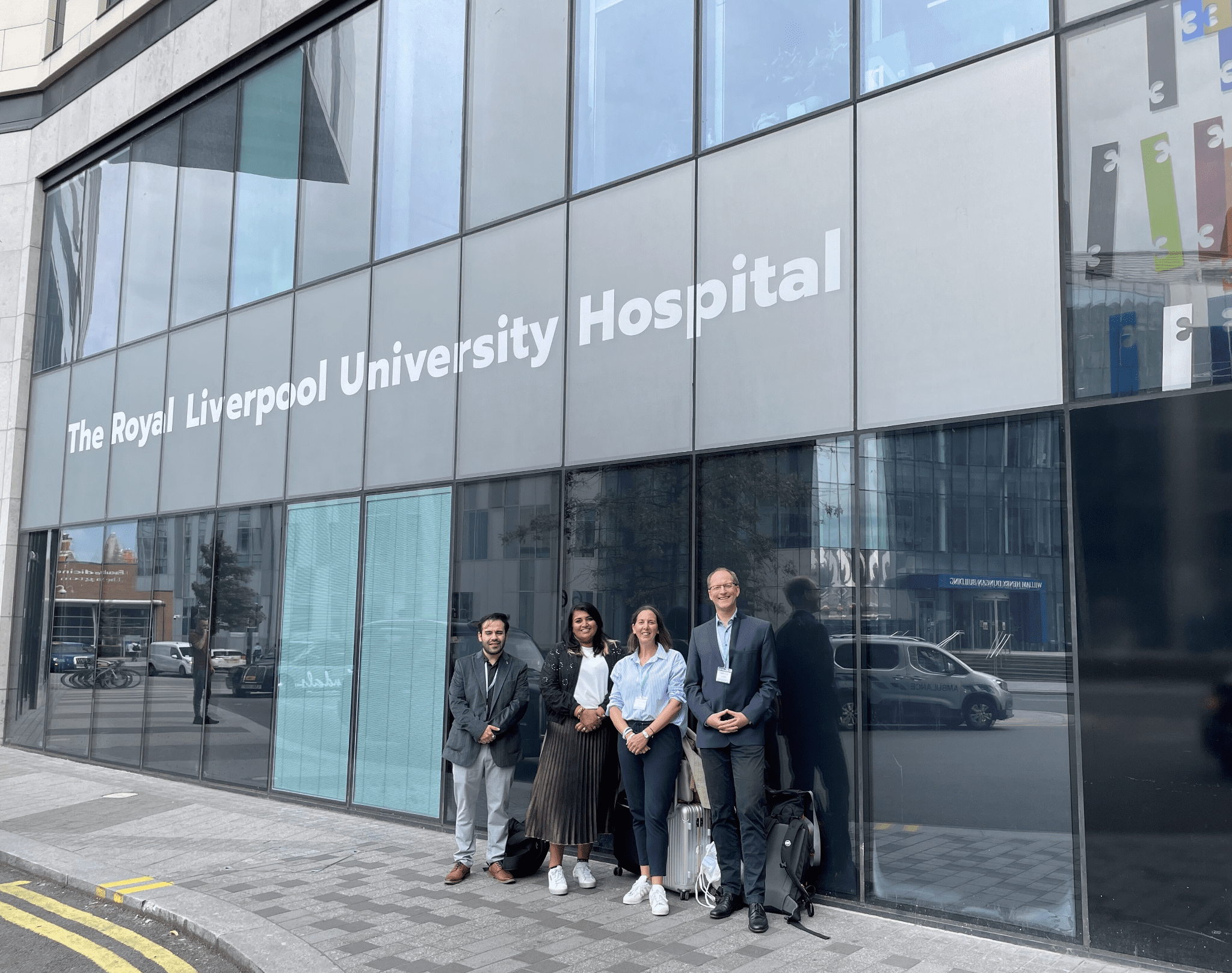

Physically, the buildings still stand on the campus map – some of them serve as administrative or educational spaces. But what is more important is that the scientific approach embedded in the Johnston Laboratories became part of the university’s DNA. Biochemistry remains one of the most powerful areas here, and the Faculty of Life Sciences regularly features in international rankings.

The idea of interdisciplinarity, which the Laboratories implemented long before it became a trend, is also still very much alive. The university’s modern projects often unite specialists from medicine, engineering, chemistry, and computer science. The influence of the laboratories is still felt in every project that begins with a simple question: “What if we tried it this way?”.