Have you ever wondered where the global fight against malaria, tropical fever, or other “exotic” diseases began? The answer you’re about to read on iliverpool.info will surprise you: it all started in Liverpool. It was here, at the end of the 19th century, that the world’s first school of tropical medicine was founded. Its name clearly showed the institution’s purpose – the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (or LSTM).

At a time when medicine was just learning to be a science, LSTM became a launching pad for scientific breakthroughs, international cooperation, and a deep transformation of medical ethics. Its history is both a look into the colonial past and an example of how science can change itself for a more just future.

How It All Started: Tropics, Empire, and Mortality

The late 19th century. The British Empire was in its prime, maritime trade was flourishing, and Liverpool was one of its key ports. However, behind the imperial ambition was a disturbing statistic: a high mortality rate among colonial officials and workers in tropical regions. Diseases like malaria, yellow fever, and dysentery were literally wiping out Europeans in Africa, Asia, and South America. This became both a humanitarian and an economic problem: it was in the empire’s interest to have a living and healthy workforce.

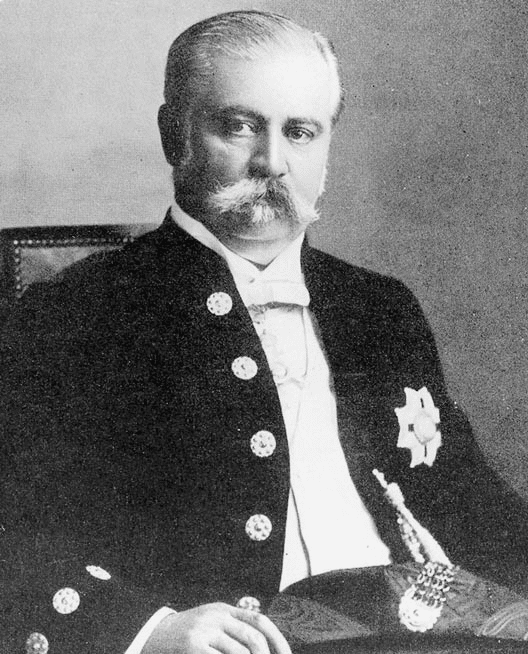

That’s why, in 1898, British politician Joseph Chamberlain called for the creation of institutions capable of studying and treating “tropical diseases.” In Liverpool, Alfred Lewis Jones, a merchant and philanthropist, immediately responded to this call and agreed to fund a school of tropical medicine. Thus, in November 1898, the world’s first institution specializing in this field came into being. A few months later, it opened its doors to the first students, and its first teachers – including the distinguished Sir Ronald Ross, who proved that malaria is transmitted by mosquitoes – laid the foundations of a new discipline.

While from a modern perspective, all of this might seem like part of the colonial machine, it’s hard to deny that it was then and there in Liverpool that the approach to medicine as a global phenomenon began to take shape. The history of LSTM is an example of how an imperial need gave rise to knowledge that would eventually work for the well-being of all humanity.

From Colonial Tool to Scientific Player

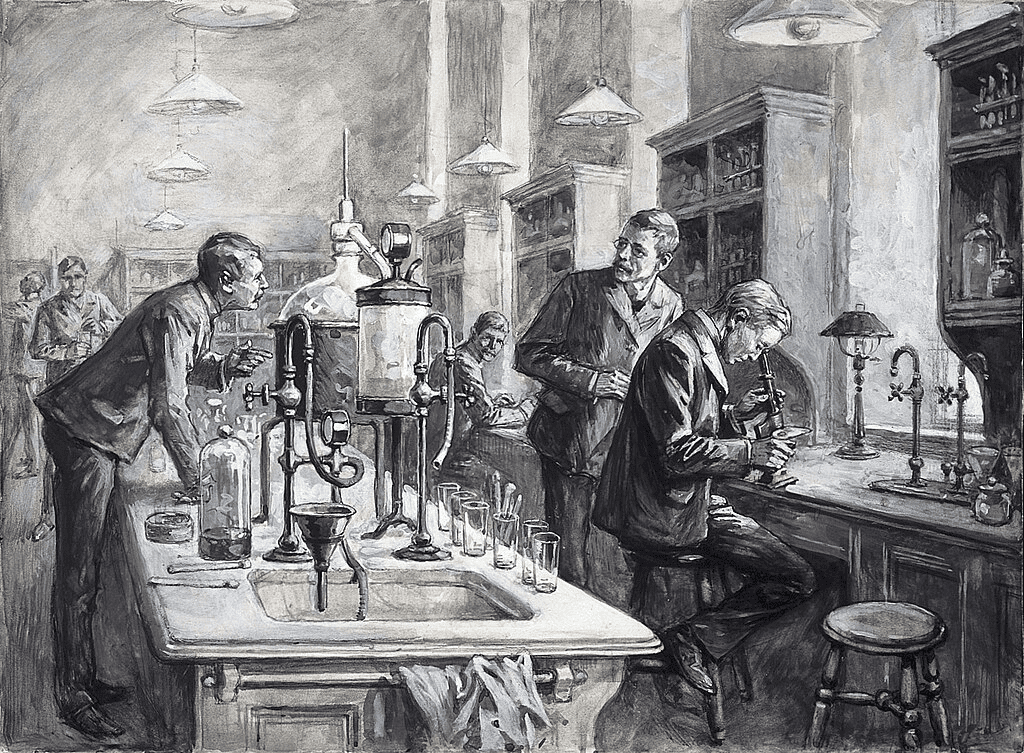

In its first decades, LSTM indeed worked in the interests of the empire. Its specialists researched diseases that threatened British soldiers, officials, and entrepreneurs in the colonies. But over time, the school increasingly became a science-centric institution. One of the symbols of this shift was the research centre opened in Sierra Leone in 1921 – the school’s first overseas laboratory. It was there that scientists discovered that onchocerciasis (so-called “river blindness”) is transmitted by the bites of black flies – a discovery that changed approaches to controlling the disease.

Throughout the 20th century, the school not only expanded the geography of its research but also deepened its methods. It became a centre where medicine became applied: field studies, analysis of transmission vectors, epidemiological modelling. In the post-war period, especially from 1946 when Bryan Maegraith took over as head of LSTM, the institution began to actively rethink its role. His motto was:

“Our influence in the tropics must be exerted in the tropics themselves.”

This became a policy statement for the school. It meant, among other things, that LSTM would increasingly focus on real health changes in tropical regions, not just on gaining knowledge useful to Western countries.

By the 1990s, the school had a world-class scientific reputation. Here, new insecticides against mosquitoes were developed, and strategies were created to combat malaria and other infectious diseases. At the same time, the understanding became clearer: scientific discoveries have true value when they serve the common good, not the narrow political or economic interests of individual states.

Science and Responsibility: A New Face for LSTM

In the early 21st century, the colonial legacy that had long been ignored began to be openly discussed within LSTM. The institution, which started as a practical tool of imperial medicine, began to openly analyse its own past. A clear statement appeared in strategic documents: the school must become an anti-racist organisation. This path is not about reputational gestures, but about re-evaluating approaches to cooperation, education, and research.

The school’s official website states directly:

“Our origins – like the history of Liverpool itself – are rooted in colonialism and imperialism. And to move forward, we must acknowledge that past.”

This phrase is backed by real actions: re-evaluating curricula, including the perspectives of researchers from tropical regions, and institutional cooperation based on equality.

A prime example is the partnership with Malawi, where LSTM works not as a “big brother” but as an equal partner in clinical and community projects. This approach means, on one hand, a deeper respect for the local context, and on the other, an increase in the effectiveness of medical interventions. The focus, of course, is on science, but also on ethics. All of this is changing the face of LSTM. The school is an excellent example of how institutions with imperial roots can evolve towards genuine solidarity with the whole world.

LSTM Today: Knowledge That Saves Lives

Today, LSTM is a powerful scientific and educational institution with a global reputation. Its annual budget exceeds £100 million, its research project portfolio is worth over £220 million, and its partners include giants like the Gates Foundation, Wellcome Trust, and governments of dozens of countries. But the most important thing is not its size, but its impact.

The school continues to be a bastion in the fight against malaria, antibiotic resistance, tropical viruses, and the consequences of pandemics. It develops new vaccines, tests healthcare strategies for countries with limited resources, and trains specialists who return home with the tools for real change.

In addition to its research, LSTM is a place of learning: hundreds of students from all over the world participate in its master’s and doctoral programmes every year. They include future doctors, field epidemiologists, and global health management specialists. It is important that the school’s educational approach is not a one-way transfer of knowledge from teacher to student, but an equal dialogue. Some of the training takes place directly in tropical countries, at partner clinics and research centres. LSTM graduates work in the world’s most critical locations – from epidemic-stricken regions of Africa to post-conflict zones in Asia.

In the context of global challenges, LSTM has become a moral authority in the field of international public health. The school’s history proves that even an institution with a difficult past can change and become an example for others – in both science and humanity.

In Conclusion

Despite its venerable age, LSTM remains a place where the future of medicine is created. The modern LSTM model combines field research, education, and technology – all with a focus on practical results. At the same time, the demand for working at LSTM is growing: the school regularly opens vacancies for researchers, clinicians, and data analysts who are ready to work at the intersection of science and ethics. And what about Liverpool? Our city has every right to be proud that LSTM was born here. Moreover, today the centre of Merseyside is not limited to its contribution to science. It is also actively developing cultural projects, including inclusive theatres.