What is the human brain and how does it work? There’s no single formula for an answer, yet pioneers like Sir Charles Scott Sherrington knew more than their contemporaries, pushing science forward. He lived a long and brilliant life spanning the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, leaving behind scientific theories that transformed our understanding of how the body functions and how the human mind thinks. His ideas on the integrative action of the nervous system, the concept of the synapse, and the study of reflexes laid the groundwork for the nascent field of neuroscience. Sherrington’s connection to Liverpool was pivotal, as it was there that his scientific work truly took off. Who was this scientist who spoke of reflexes as a symphony of the body? Read on for the full story at iliverpool.info.

From Ipswich to Liverpool: Charles’s Journey as a Scientist

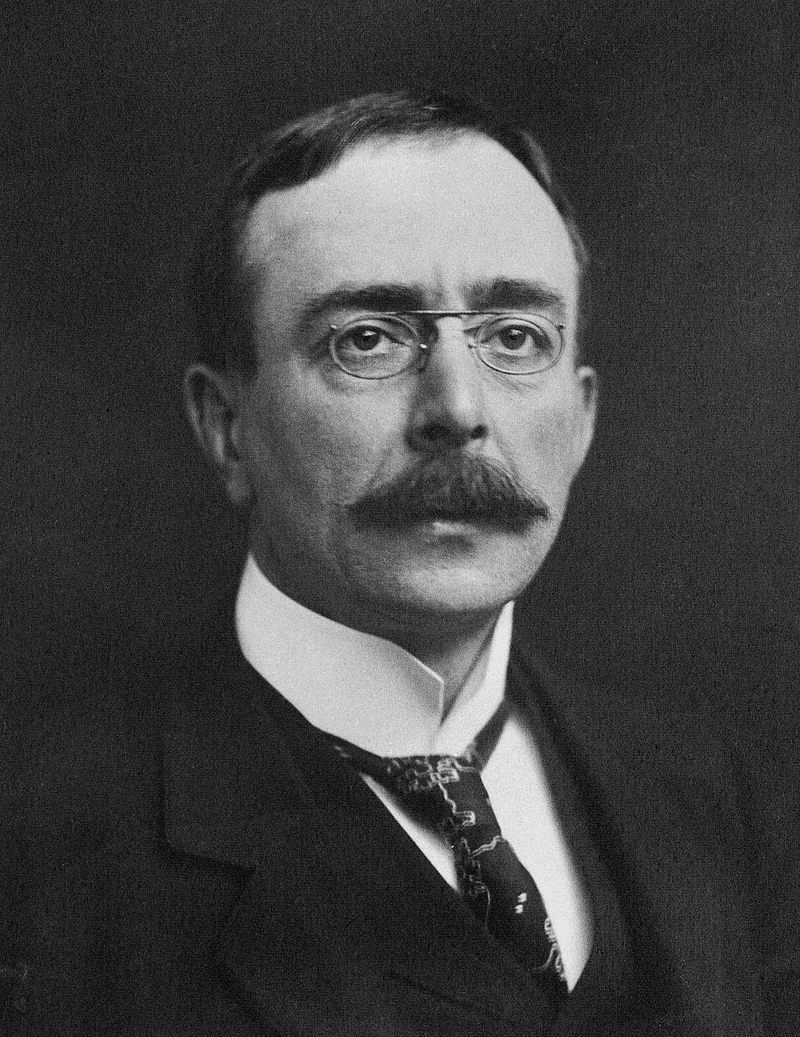

Charles Sherrington was born in London in 1857, spending his childhood in Ipswich where he was raised in the family of a humanist physician. From a young age, he showed a keen interest in natural sciences, but his real breakthrough came at Cambridge. There he studied physiology, focusing on the nervous system, and quickly caught the attention of his lecturers with his unconventional thinking.

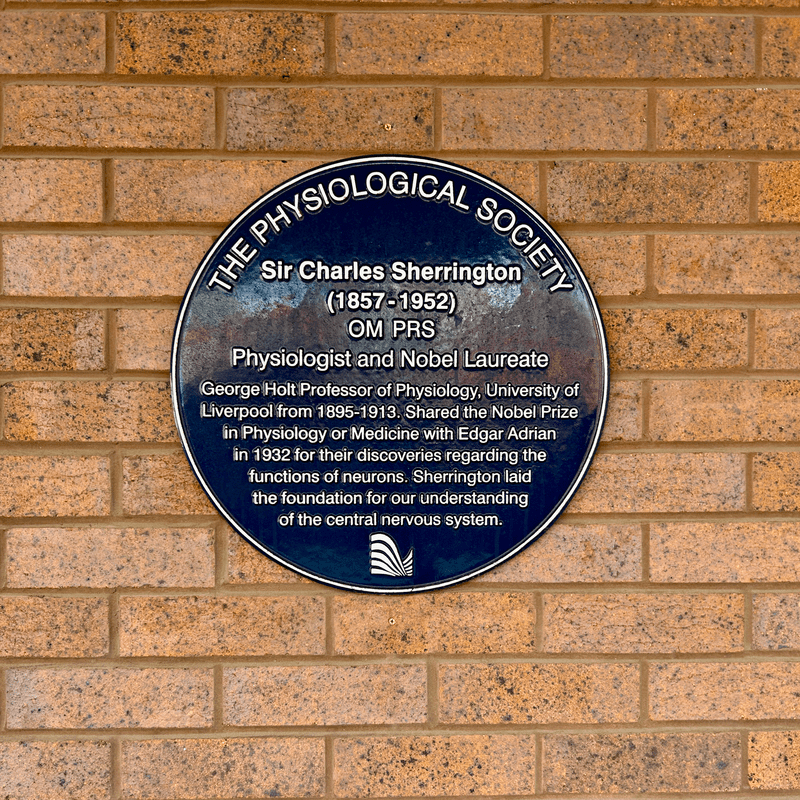

After graduating, Sherrington worked in various laboratories, including the Brown Institute in London. But a true turning point came in 1895 when he was offered a professorship at the University of Liverpool. The city, with its industrial spirit, dynamic energy, and openness to new ideas, proved to be the perfect environment for his scientific leap forward.

In Liverpool, Sherrington taught his favourite subjects and established a new research school. It was here that his most important ideas on how the body processes nerve impulses began to form. In essence, Liverpool marked the start of Sherrington’s emergence as a thinker of global significance.

The Nervous System as a Symphony: The Scientific Legacy of Charles Scott Sherrington

While in Liverpool, Sherrington focused on studying what was then considered one of the human body’s most mysterious systems: the nervous system. He was dissatisfied with the simplistic view of reflexes as merely mechanical reactions to stimuli. He saw these processes much more broadly—as a coordinated interplay of many components, much like an orchestra. This is why his work, “The Integrative Action of the Nervous System” (1906), was a landmark achievement: it was the first to systematically argue that the nervous system doesn’t just transmit signals, but synchronises the actions of the entire body.

One of his most significant achievements was the introduction of the term ‘synapse’, which he borrowed from Greek. With this word, Sherrington described the point of contact between neurons where an impulse is transmitted. This was the key to understanding the complex architecture of neural communication. Everything we know today about neural networks—from memory to motor skills—in one way or another, started with his research.

Equally important was his concept of reflex interaction, particularly the phenomenon of reciprocal muscle inhibition. According to this, when one muscle is activated, its antagonist is automatically inhibited thanks to central control from the spinal cord. This was a radical departure from the idea of reflexes as simple, closed arcs. Sherrington proved that all reactions are integrated and coordinated by higher centres.

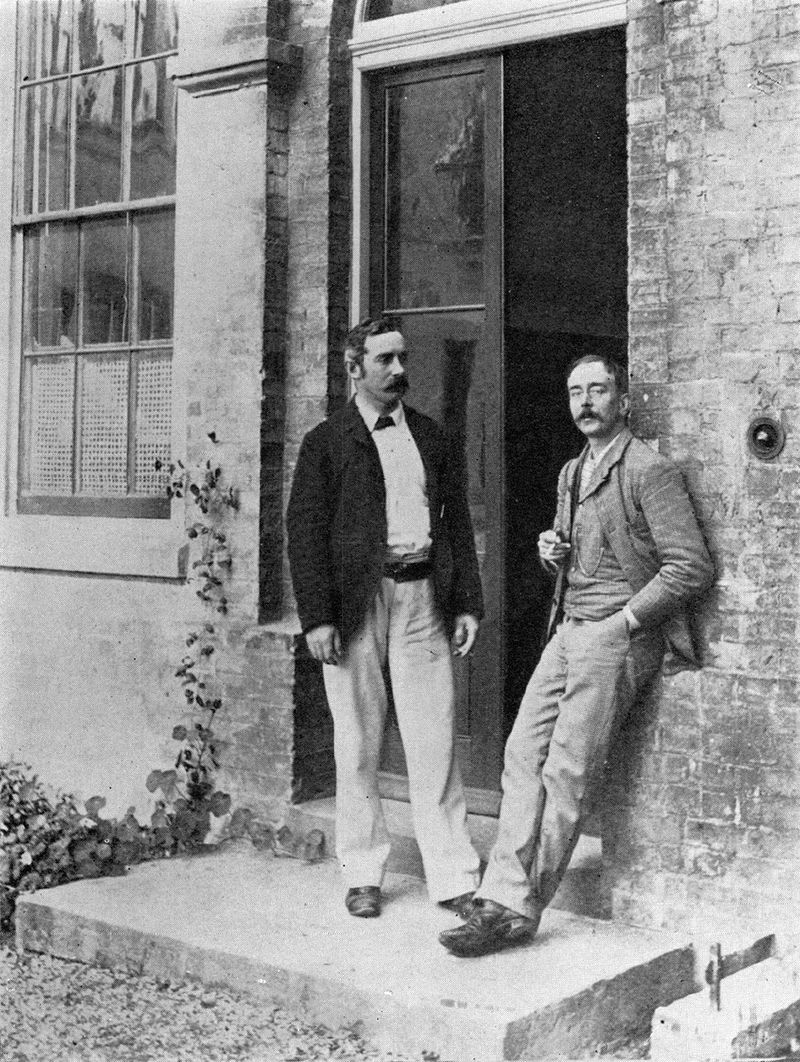

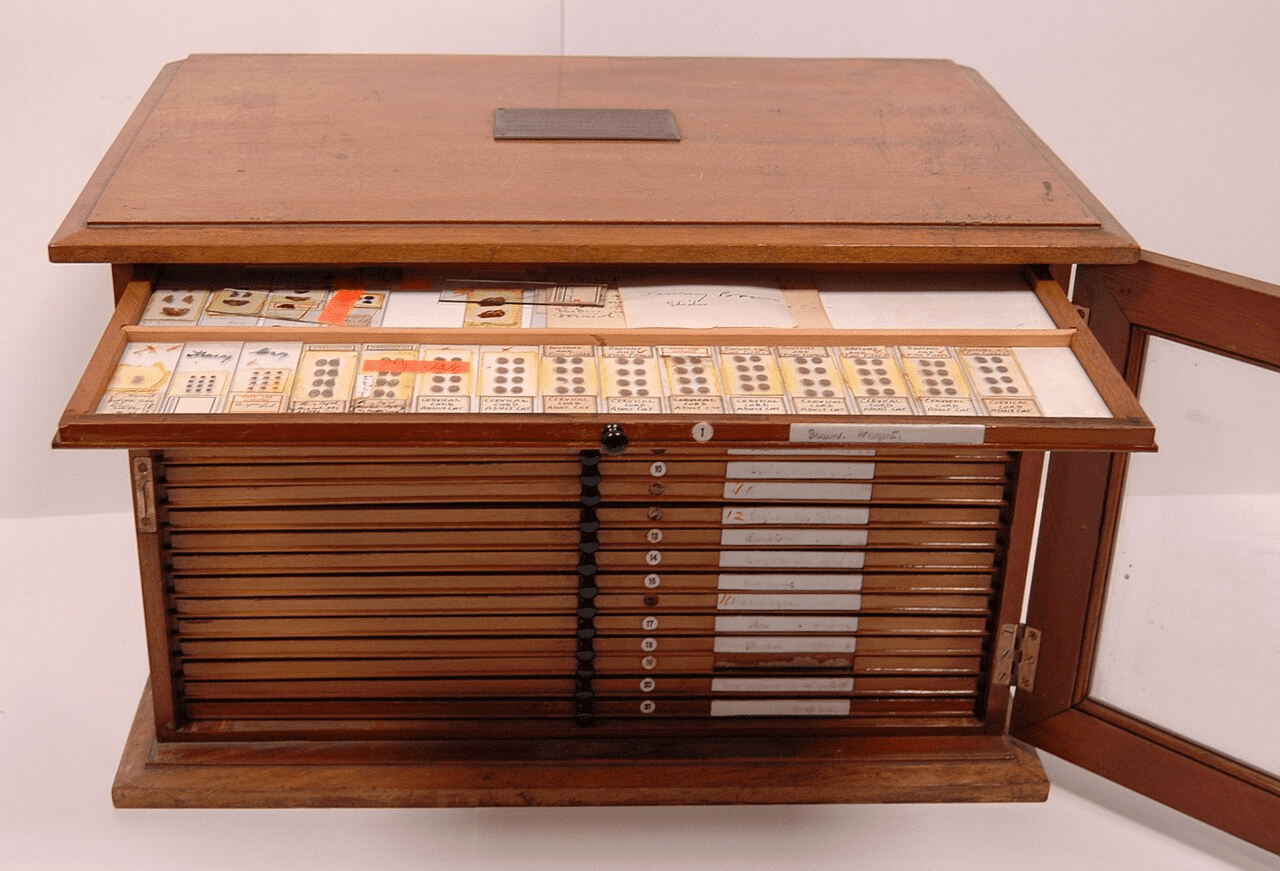

In his research, he used innovative methods, such as pinpoint stimulation of muscles in animals, which allowed him to trace the pathways of signals in detail. He conducted some of these experiments in Liverpool, where he had access to a well-equipped laboratory and the support of young scientists. This period laid the foundation for his later academic career, which he continued at Oxford.

For his time, Sherrington was a revolutionary. His views on neural interaction predated the advent of electron microscopy and electrophysiology. He thought in a systematic and imaginative way, unafraid to combine biology, philosophy, and even music, which made his research conceptually profound.

Sherrington’s Nobel Prize and Recognition

By the 1930s, Charles Sherrington was a recognised authority in physiology, but true international acclaim came with the Nobel Prize. In 1932, he shared it with fellow British scientist Edgar Adrian for their research into the functions of neurons. The committee highlighted that their work offered a new perspective on how a nerve impulse is transmitted and converted into physiological action. Sherrington brought science to a point where the body’s behaviour could be described not just as a series of reactions, but as a finely tuned system of connections.

This award was a recognition of both Sherrington’s personal achievements and the school of thought he had created. From Liverpool to Oxford, dozens of his students and followers worked in various labs. He was a great inspiration, not just directing research but thinking alongside his team. His style—a blend of intellectual rigour and philosophical depth—stood out even among the scientists of his era.

In addition to the Nobel Prize, the scientist received many other honours. He was elected president of the Royal Society of London, one of the world’s most prestigious scientific institutions. He was awarded the Copley Medal, the Royal Medal, and the Order of Merit—a distinction given for outstanding contributions to science, art, or public life. He also received a knighthood, which, however, did not change his humble nature. Charles remained a modest man.

In fact, Sherrington was cautious about awards. For him, the primary question was always “how to better understand life,” not “how to get an award for a discovery.” His mind was not focused on achieving fame, but on finding harmony between nature and reason. And this is perhaps his most important quality as a scientist: to feel the world, rather than be content with merely describing it.

Man Over Machine: Philosophy and Humanism

In his later years, Charles Sherrington became increasingly drawn to philosophical reflections. His science was never limited to physiology alone; even as a student, he was interested in classical literature and the humanities, and later, in ethics, religion, and poetry. All of this eventually culminated in his book, “Man on His Nature,” published in 1940, which became a summary of his worldview. In it, he poses a fundamental question: what does it mean to be a person, a thinking being in a body made of muscles, neurons, and bones?

Sherrington suggests that consciousness is something deeper and more delicate than science can explain. He writes about the beauty of nature, about human moral responsibility, and about the boundary between the biological and the spiritual. The style in this book is no less imaginative than in his scientific works: he draws on poetic allusions, uses metaphors, and addresses the reader as a conversational partner.

The philosophical ideas expressed in “Man on His Nature” were not detached from science. On the contrary, it was his deep understanding of physiology that enabled Sherrington to question the limits of that very science. He didn’t oppose the body and mind; instead, he tried to show how closely they are connected. This is where his humanist perspective lies: to see a person not as a mechanism, but as a holistic organism with will, intuition, and self-awareness.

These views impressed both fellow scientists and philosophers. The book became popular with a wider intellectual audience. Even after Sherrington’s death in 1952, his works were still widely cited, reprinted, and commented on. Above all, they were seen as a vibrant and inspiring thought: that consciousness does not oppose nature but is its highest expression. This may be why Liverpool is home to such eco-innovations as the “Hemisphere” or the artificial floating eco-island.