Few people today remember that long before electricity, Liverpool was already powered by water – quite literally. At the very heart of its docks, amidst the chimneys and cranes, operated a hydraulic network that was the city’s true engine. The website iliverpool.info answers questions about how hydraulics brought the port to life, where its traces are hidden today, and why this story is unexpectedly returning in the future. Let’s start from the very beginning – with an innovation that was ahead of its time.

How Hydraulics Transformed Liverpool: Sci-Fi from the 1880s

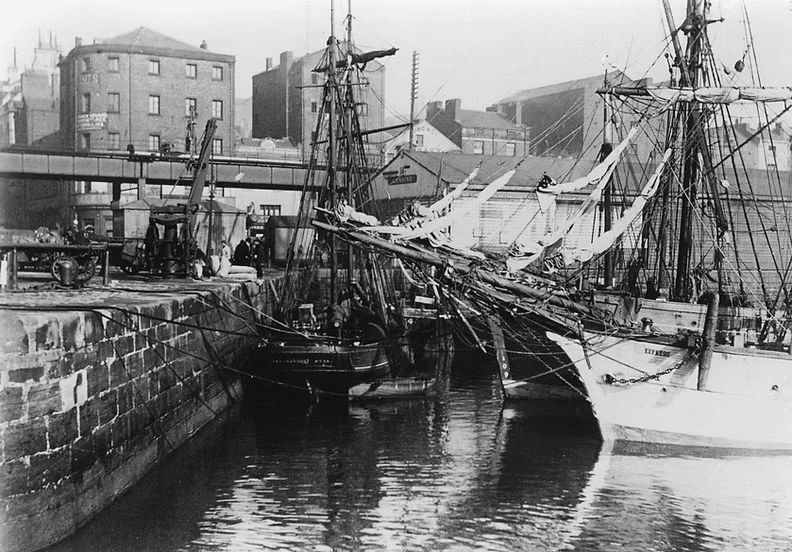

The late 19th century was a time when coal-fired steam was still the queen of energy, and electricity was just gaining momentum. It was then that a system appeared in the Merseyside docks that could have seemed like something out of science fiction – a centralised hydraulic network. It was created to power the port’s infrastructure: cranes, lifts, and lock gates, all using pressurised water. The idea was brilliant in its simplicity – to use the natural force of fluid instead of ropes, horses, and levers.

In 1885, the Liverpool Hydraulic Power Company was founded, and by 1888, its system was officially operational. Over 30 miles of steel pipelines delivered water at a pressure of 48 bar (which is more than a modern fire hose) to hundreds of hydraulic machines across the city. Street manholes, under which these pipes were hidden, can still be found if you look carefully while walking through Liverpool’s streets.

For its time, this was a true engineering revolution. The city embraced cutting-edge technology, becoming a pioneer in the widespread implementation of hydraulic power in urban life. While the docks of other cities were still contemplating how to harness water pressure, Liverpool had already put it to full use.

The Pulse of the Docks: What Powered the System

For hydraulic power to truly function as the city’s circulatory system, it needed “hearts” – pumping stations. Two main ones were located at King’s Dock and Waterloo – where today someone might be enjoying coffee or strolling along the waterfront, steel pumps once beat, moving hundreds of thousands of gallons of water daily. Later, another was added near Albert Dock, and this building, with its distinctive brick chimney, still stands today.

These stations fed almost 30 miles of pipeline that ran beneath the city. Inside, three-stage pumps pushed water into accumulator towers, and from there, under pressure, it was delivered to consumers – cranes, hoists, and lock gates. The network operated almost like a power station, but instead of electricity, there was water, and instead of wires, there were pipes. By the early 20th century, the system served over 400 connected mechanisms.

This hydraulic infrastructure maintained its efficiency until the 1960s. As electricity fully took over, the pumping stations were gradually converted to electric drives. It was a gentle transition, not an abrupt end – something akin to the slow fading of an era. And although the network was finally shut down in 1971, its logic remained relevant: the use of centralised resources to support urban functionality – an idea that sounds very modern once again.

Traces of the Hydraulic Past

Liverpool, as befits a city with character, has not just preserved traces of its engineering past but has made them part of the urban landscape. One of the most striking monuments is the old pumping station near Albert Dock – today it has been transformed into a pub aptly named The Pump House. Its tall, unmissable brick chimney has become a kind of beacon for those who want to experience the spirit of the industrial era.

Another historic structure is the accumulator tower at Wapping Dock. It has remained almost unchanged and, despite its restrained architecture, is technically unique: inside, giant pistons with levers once stood, maintaining pressure for the entire system. It was a hydraulic battery in the literal sense. And there are many such objects in the city – not just one or two: if desired, they can be explored like a route of engineering archaeology.

These structures are proof that the city once lived and breathed thanks to water. They serve as a reminder that hydraulic power is a living technology that literally kept entire districts in motion. And even today, as we pass by these towers and pipes, we witness how the engineering ingenuity of the past permeates the present.

Water Returns: The Future of Tidal Energy

The irony of history is that Liverpool is once again looking to water – this time not as a mechanical drive, but as a source of clean energy. The Mersey Tidal Power project, currently being prepared for implementation, aims to become one of the largest tidal energy facilities in the world. Its idea is to build a giant barrage system that will harness the power of the River Mersey’s tides to generate electricity.

The potential is impressive: up to 2 billion kilowatt-hours per year – enough to power almost a million households. But it’s not just about the numbers. This is a continuation of the same hydro-story that began in the 1880s: once again water, once again Liverpool, once again cutting-edge technology.

And if once water pressure moved ports and cranes, now the ocean current is capable of powering entire regions. This is a return not to the past, but to the future – with the same faith in the power of engineering that once made this city a pioneer. Liverpool is once again choosing energy that comes from the depths – only now not through pipes, but through transformers.