At the height of the pandemic, when panic often outweighed a systematic approach, Liverpool launched a bold experiment: voluntary mass testing for all residents. This initiative helped to reduce the number of infections and hospitalisations in the city and became a model for other countries. How did it all begin, who was behind this large-scale operation and what lessons were learned? Read on to find out more on iliverpool.info.

How Liverpool Implemented a Bold Idea

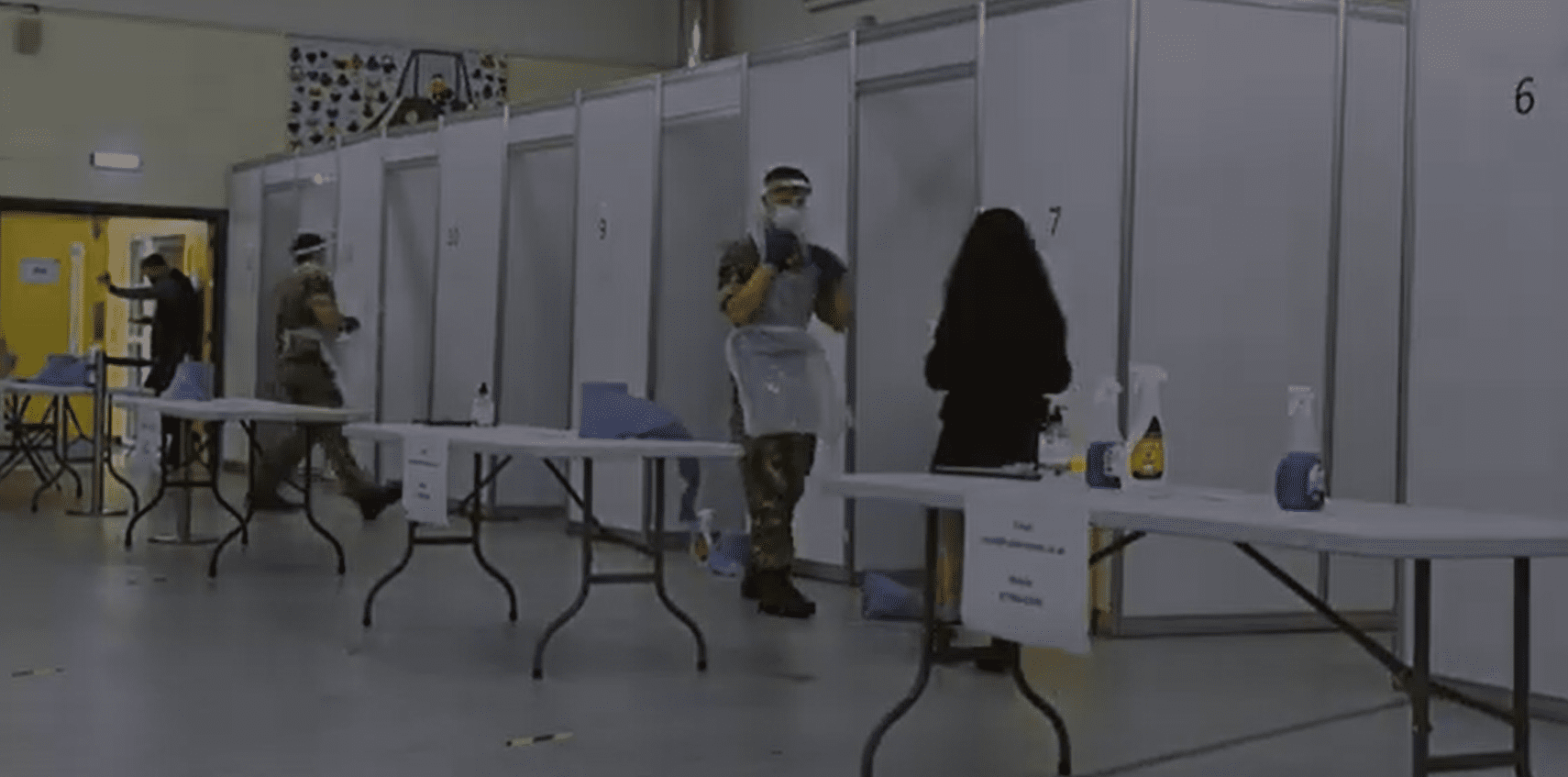

It all started with a proposal to make Liverpool a pilot site for a new COVID-19 strategy: mass testing for asymptomatic individuals. The UK government supported the idea, and its implementation fell on the shoulders of the local authorities, the NHS, the University of Liverpool and the army. In record time, over 40 testing centres were opened in the city, with more than two thousand military personnel helping with logistics, navigation and security.

The programme was named COVID SMART and it truly was ‘smart’: it combined scientific expertise with practical tools for the rapid detection of the virus. The focus was on lateral flow tests – which were fast, convenient and cheap, though less accurate than PCR tests. They could be taken without an appointment, free of charge and painlessly, with results available in just 30 minutes.

The key to it all was the approach: instead of waiting for people to come in with symptoms, the city went on the offensive, identifying hidden cases. It was a turning point, transforming the city from an industrial landscape into a laboratory for the future of public health.

The Numbers That Speak for Themselves

The results of COVID SMART proved that local initiatives can change national policy. In just a few months of testing, more than 283,000 Liverpool residents participated – about 57% of the total population. Almost half of them were tested more than once.

But the main thing was the impact. According to researchers at the University of Liverpool, the programme contributed to a 21% reduction in infections, and the number of hospitalisations in the city fell by almost a quarter. In the first month of the pilot alone, 239 hospitalisations were prevented and thousands of asymptomatic carriers were identified.

It wasn’t without criticism. The rapid tests that formed the basis of the programme had lower sensitivity than PCR tests, meaning they could miss some infected people. However, researchers insisted that the most important factors were not perfect accuracy, but scale and speed. One positive result, obtained in 30 minutes, could stop dozens of further infections. Ultimately, it was these ‘imperfect but effective’ measures in Liverpool that showed how science can work in real time on the city’s streets.

The People Who Made It Possible

Behind the dry figures lie human stories. The COVID SMART programme could not have been implemented without the cooperation of dozens of institutions and thousands of ordinary people. The heart of the initiative was the University of Liverpool, which promptly analysed data and helped to adapt the process in real time. It was there that a phrase was coined that perfectly captured the essence of what was happening:

‘Perfection should not stand in the way of the good.’

On a practical level, everything relied on a partnership with the NHS, the city council and the army, which for the first time in peacetime history was involved in a large-scale medical campaign. Their role was logistics, deploying mobile points and coordinating processes on the ground. But the most valuable contributors were the volunteers: thousands of city residents who came to help, inform and support the elderly and vulnerable.

At the same time, the programme sharply highlighted social contrasts. Areas with lower incomes and higher infection rates were less covered by testing – not everyone had the opportunity or motivation to be tested. This was a painful reminder that even the best initiatives require trust, accessibility and fairness.

All this made COVID SMART a real social experiment – showing how the community, science and the healthcare system can work together.

What Was Learned from Liverpool’s Example

The pilot programme in Liverpool ended, but its impact did not. On the contrary, this case became the starting point for the wider implementation of mass testing throughout the UK. The government adopted the model of rapid local solutions, and Liverpool’s experience showed that even in the midst of a crisis, it’s possible to act quickly, systematically and effectively.

One of the main lessons was flexibility. The city skillfully adapted to the new reality, which allowed it to stay one step ahead. The second was the importance of the trust of local people: there would have been no effect without community support and the thousands of people who believed in the common cause. The third was the partnership between sectors: science, the army, the municipality and volunteers – they all worked as one system.

By the way, this is not the first time Liverpool has shown an ability to mobilise in critical moments – it was also the case during the smallpox outbreak, when the actions of Dr Edward Hope saved the city. And during COVID-19, some local businesses, particularly in the pub trade, faced a real challenge, but they were able to adapt to the new conditions.

Today, this experience is being studied by researchers and politicians in various countries, and Liverpool itself has become an example of how a city can serve as a laboratory for new solutions. It’s possible that it is precisely in such stories that the key to readiness for the next pandemics lies.