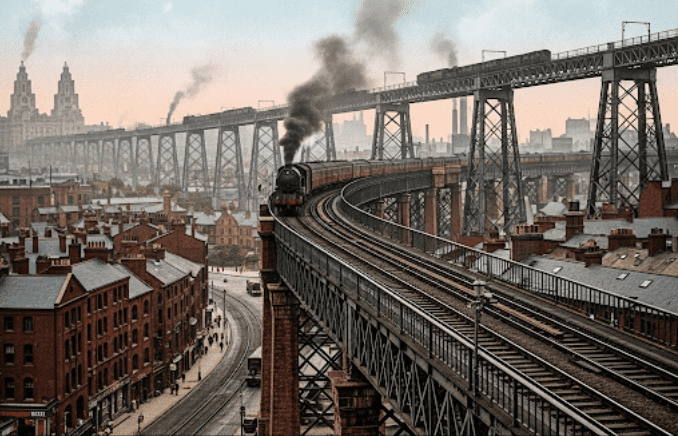

Imagine: a gleaming electric train speeding along a narrow metal bridge high above the river docks. Below, thousands of stevedores and port cranes; above, thick smoke from steamships; and all around, the wind off the Irish Sea. This isn’t a scene from a sci-fi film, but Liverpool in 1893. Here, the world’s first elevated electric railway was launched – it soared above the city on slender iron legs, glowed at night, had automatic signals, and even an escalator at the station. It was so popular that it was dubbed “the dockers’ umbrella” because it so thoroughly covered the port areas. How this engineering marvel came to be, and why not even a shadow of it remains today – read on at iliverpool.info.

A Project of the Future: How and Why the First Overhead Railway Emerged

In the 1890s, Liverpool was suffocating – both literally and in a transport sense. Along the Mersey, where huge port warehouses stretched, movement became increasingly difficult. Horse-drawn transport, pedestrians, wagons, and endless queues of cargo – the city, which handled dozens of ships daily, began to resemble a clockwork mechanism without a pendulum.

Then, a group of engineers and financiers proposed a plan: to lay a railway line above ground, right along the docks. Not in a tunnel, like in London, and not far from real life, but on a high viaduct – at second-floor level. And not with steam locomotives, which could set cargo on fire, but with electric trains. This solution seemed so audacious that it was initially perceived as fantasy. But the Liverpool Overhead Railway company not only developed but also implemented the project in four years.

By 1893, the first carriages were moving above the city. The tracks stretched along all the main docks – from Bramley-Moore to Dingle. Every passenger had a window onto an industrial symphony: warehouses, cranes, steamships, a cacophony of sound. This overhead railway looked as if it had stepped out of the pages of Jules Verne, yet it truly ran on schedule, just like a regular bus.

In the Air Above the City: What Made the Railway an Icon of Its Time

At first glance, the Liverpool Overhead Railway looked simple: a metal structure on pillars, narrow platforms, light carriages. But it was precisely this simplicity that made it a breakthrough. For the first time in history, trains ran on electric traction not underground, but in plain sight – and without the smoke, soot, and clatter of steam engines. At night, the railway glowed with electric lights, and at James Street station, an escalator was installed – the first in Great Britain. These were world-class innovations!

A journey cost a few pence – making it accessible to clerks and dockers alike. Because of this, the railway quickly earned the nickname Dockers’ Umbrella – the “Dockers’ Umbrella.” It literally covered the docks, protecting from rain and allowing workers to get from one end of the port to the other in a matter of minutes. Instead of walking five or six miles, workers simply stepped onto the platform and boarded a carriage.

The carriages were small, wooden, with narrow aisles, but they had separate compartments, and even ventilation – at least at the time, this was considered comfortable. During peak hours, trains ran every few minutes, and carried up to 20 million passengers a year. For comparison: the New York subway was only being planned, and in Paris, there wasn’t even a project.

The Liverpool Overhead Railway became a symbol of modernity, daring, and engineering spirit for the city. And even 130 years later, it is remembered as one of the most visually striking transport systems that ever existed.

War and Decline: How the Railway Lost Momentum

By the 1930s, the overhead railway was no longer a sensation, but it remained a beloved mode of transport for tens of thousands of citizens. The carriages hadn’t changed since launch – perhaps the interiors were slightly modernised, and structures reinforced. Electrical systems were only partially updated, and platforms and tracks gradually wore out. The owning company had a limited budget, and the state – as was then customary – did not interfere with private transport.

During the Second World War, the railway withstood direct bomb hits and daily shelling. Parts of the viaduct were damaged, one station was completely destroyed. But operations did not cease: every carriage was worth its weight in gold, as the docks worked at full capacity, transporting military equipment. The railway became a critical artery between the port and the city – at that time, it was not romance, but a daily necessity.

After the war, the city began to recover, but the overhead railway did not. The carriages remained the same, only some were updated with aluminium bodies, doors began to open automatically, and some platforms were modernised. But this was not enough. In 1955, an audit was conducted: to carry out a full overhaul, over two million pounds were needed. The company did not have such money – and no one offered them help.

At this time, competition from buses and private cars grew rapidly. People sought novelty, and the overhead railway, which their parents had admired, seemed like a relic. Passenger traffic fell, income decreased, and the structures continued to age. Even those who had used the railway all their lives began to admit that its time was passing. The legend was losing momentum – slowly, but steadily.

Only Memory Remains: How Liverpool Said Goodbye to a Legend

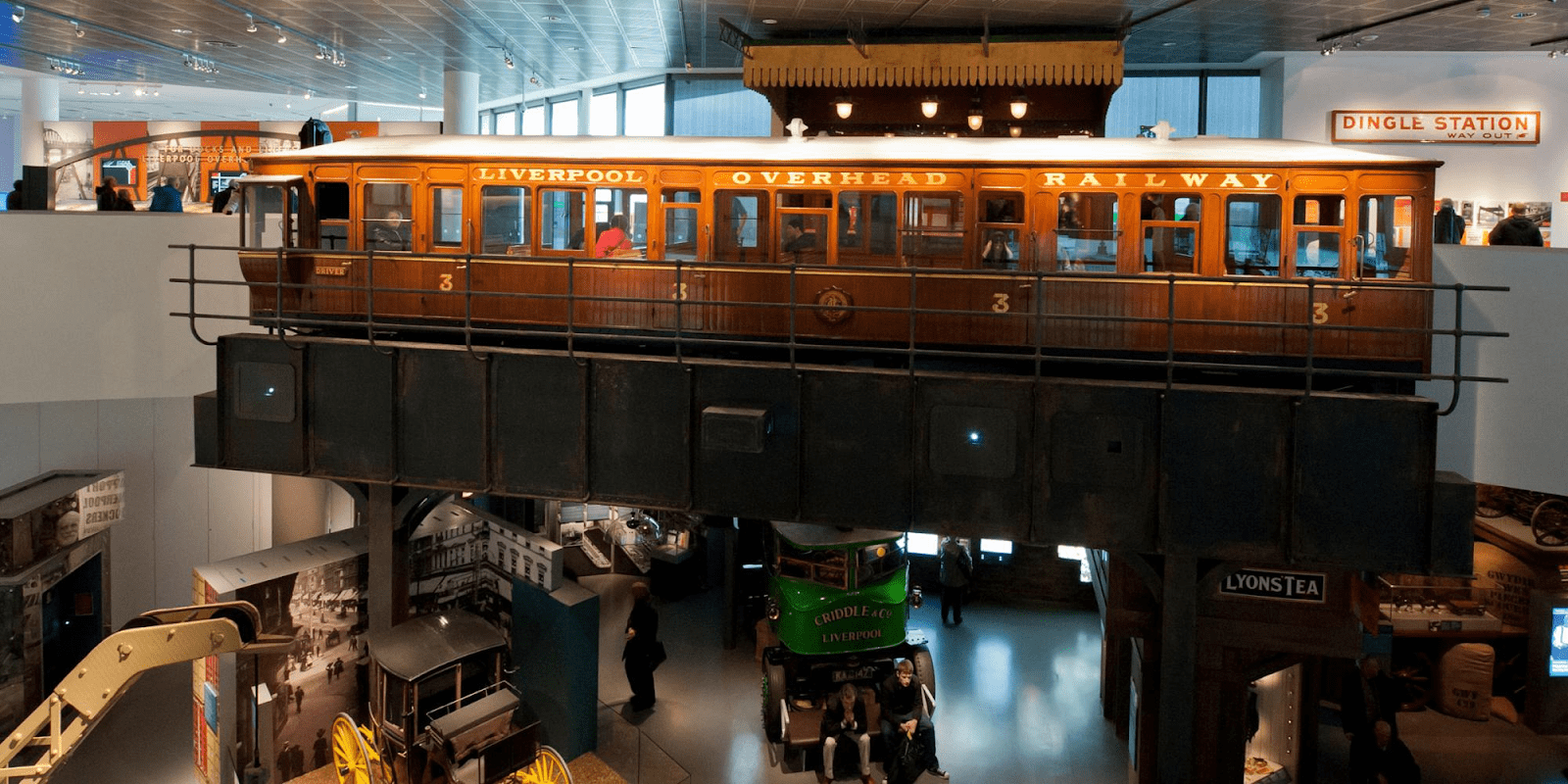

On 30 December 1956, the carriages made their final journey. Without orchestras, without fanfare – just tears in the eyes of passengers who had come to remember Liverpool flying above itself. The next day, dismantling began: section by section, bolt by bolt – taking apart what had been part of the urban landscape for decades. By the end of 1958, not a trace of the railway remained. Not a single arch, not a single pillar – everything was sold for scrap metal.

Public outrage was loud then, but belated. People signed petitions, deluged newspapers with letters, demanding the preservation of at least part of the viaduct as a monument. But in those years, there was no culture of preserving infrastructural heritage. Old things were demolished to make way for new. And the overhead railway disappeared as quickly as it had once appeared.

Only trifles survived – one carriage in a museum, signalling devices, a few drawings and models. The National Museum Liverpool still preserves parts of the equipment, and old tickets and photos are shown at exhibitions. But there is no sense of scale – what it was like to stand on the viaduct, hear the rumble of the rails, and see the docks from above. All this remained only in memories and archives.

Today, the railway is remembered with gentle irony – like an urban legend that was too progressive for its time. The idea of flying over the city in electric carriages was born in Liverpool long before the advent of high-tech. And it was destroyed not because it was bad, but because the world had not yet learned to value and preserve what was good. “We don’t know what we’ve got until it’s gone.”

The Liverpool Overhead Railway is impressive, but it’s equally surprising that in a city where an electric railway was launched in the 19th century, the authorities took so long to solve basic sanitation problems. To feel the full contrast, it’s enough to recall the story of James Newlands – a Scottish engineer who pulled Liverpool out of stench and epidemics by introducing the world’s first urban sewerage system. And if, after learning about the railway, you want to relax a bit amidst mountain landscapes and strange words – it’s worth getting acquainted with the Transcarpathian dialect: its archaisms are sometimes no less exotic than the escalator created in 1893.