Imagine a city where rain washed human waste straight out of windows into ditches, where entire neighbourhoods reeked of a cocktail of fish, smoke, and cholera, and the word ‘hygiene’ sounded like a foreign concept. That was Liverpool in the mid-19th century—and even worse before then. Yet, it was in this very port city that the story of a systemic approach to public health truly began. It’s a history that inspires doctors, urban planners, and everyday citizens today. Our article on iliverpool.info explores the courage and humanity that became the foundation of the hygienic revolution.

Liverpool’s Leap into Health: The First Medical Officer and Municipal Action

The mid-19th century. Liverpool was the beating port heart of the British Empire, a hub where goods, dreams, and… infections arrived. The population was soaring, but sanitation was virtually non-existent. People were crammed into squalid slums, without access to clean water, and with primitive or no sewage systems. Illness wasn’t the exception; it was a daily reality. In these conditions, cholera, typhoid fever, and tuberculosis ran riot, claiming a devastating toll of lives.

But Liverpool refused to surrender. In 1847, something truly groundbreaking happened: the city became the first in Britain to establish a municipal Health Department. Its first leader was Dr. William Henry Duncan. ‘Medical Officer of Health’ wasn’t just a title; it was a mission that demanded immense bravery. Duncan had to take on indifference, ingrained habits, and even powerful business interests.

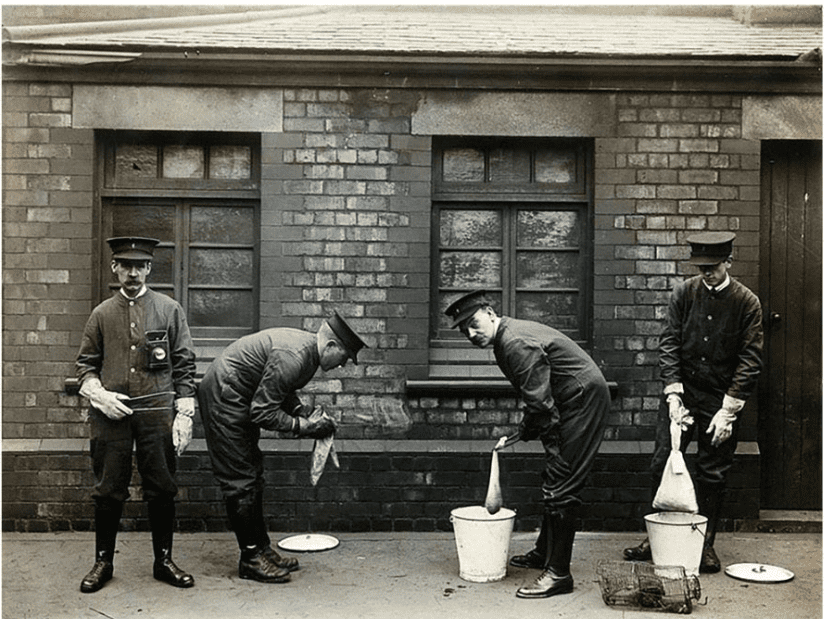

He started with something simple yet radical: collecting data, mapping disease outbreaks, and analysing living conditions. His conclusions were uncomfortable but undeniable: poverty, filth, and a lack of local government oversight were killing people faster than any virus. Duncan publicly highlighted the dangers of uncollected refuse, contaminated rainwater runoff, and damp basements where waste festered. Crucially, he proposed solutions: establishing a system of inspections, clean water provision, and proper sewerage.

His approach was revolutionary, not just for Liverpool, but for the whole of Britain. Hygiene suddenly transformed from a private concern into a public, even political, issue. The city council backed him, setting a vital precedent. This marked the birth of hygiene as a community value, not merely a personal habit.

While not every household instantly gained a sink, hope finally emerged that the city could, indeed, be clean. It all started with one doctor’s conviction that squalor wasn’t a death sentence, but a problem that could be tackled and overcome.

Institutionalising Cleanliness: The School and Chair of Hygiene (1897)

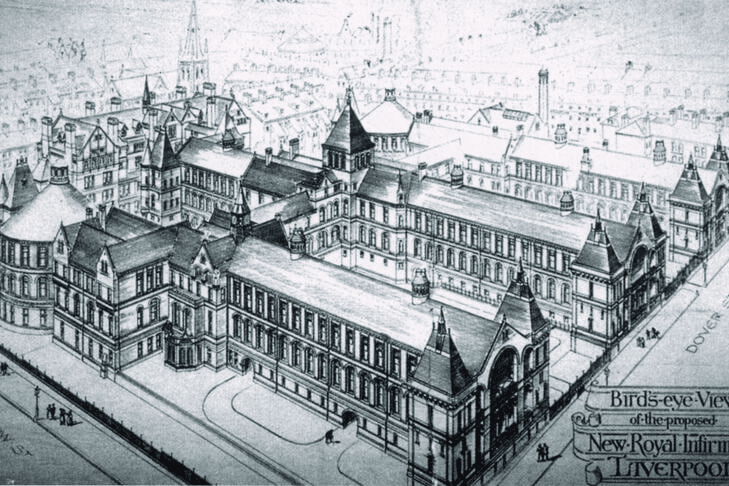

The end of the 19th century brought a fresh chapter in Liverpool’s fight for cleanliness: the city continued to battle filth and disease by making hygiene a dedicated academic subject. In 1897, the School of Hygiene was established at the newly formed Liverpool University College (which later became the University of Liverpool). This institution acted as a crucial bridge between science and action, between knowledge and practical implementation.

Significantly, the School of Hygiene was the result of a close partnership between local government and academia. The Liverpool Corporation had already set the first UK precedent in 1847 by creating a municipal public health department. The city’s leaders backed the idea that hygiene was not just a collection of tips, but a whole discipline worthy of a dedicated research chair.

So, on one side, you had the city with its pressing issues: a rapidly expanding population, overcrowded living quarters, and persistent infectious outbreaks. On the other, the academic community stepped up to investigate causes, analyse consequences, and train a new generation of doctors and health inspectors. This synergy was unique for its time; few places in Europe were taking hygiene quite so seriously.

In Liverpool, hygiene was embraced as a socially vital discipline, grounded in statistics, ethics, urban understanding, and accountability to the people. Its influence was felt even within the walls of the city council. All of this laid the groundwork for future public health innovations. It’s no surprise that Liverpool soon became the first British city where hygiene would actively shape the political agenda.

Ground-breaking Practices in the 20th and 21st Centuries: From X-rays to COVID Tests

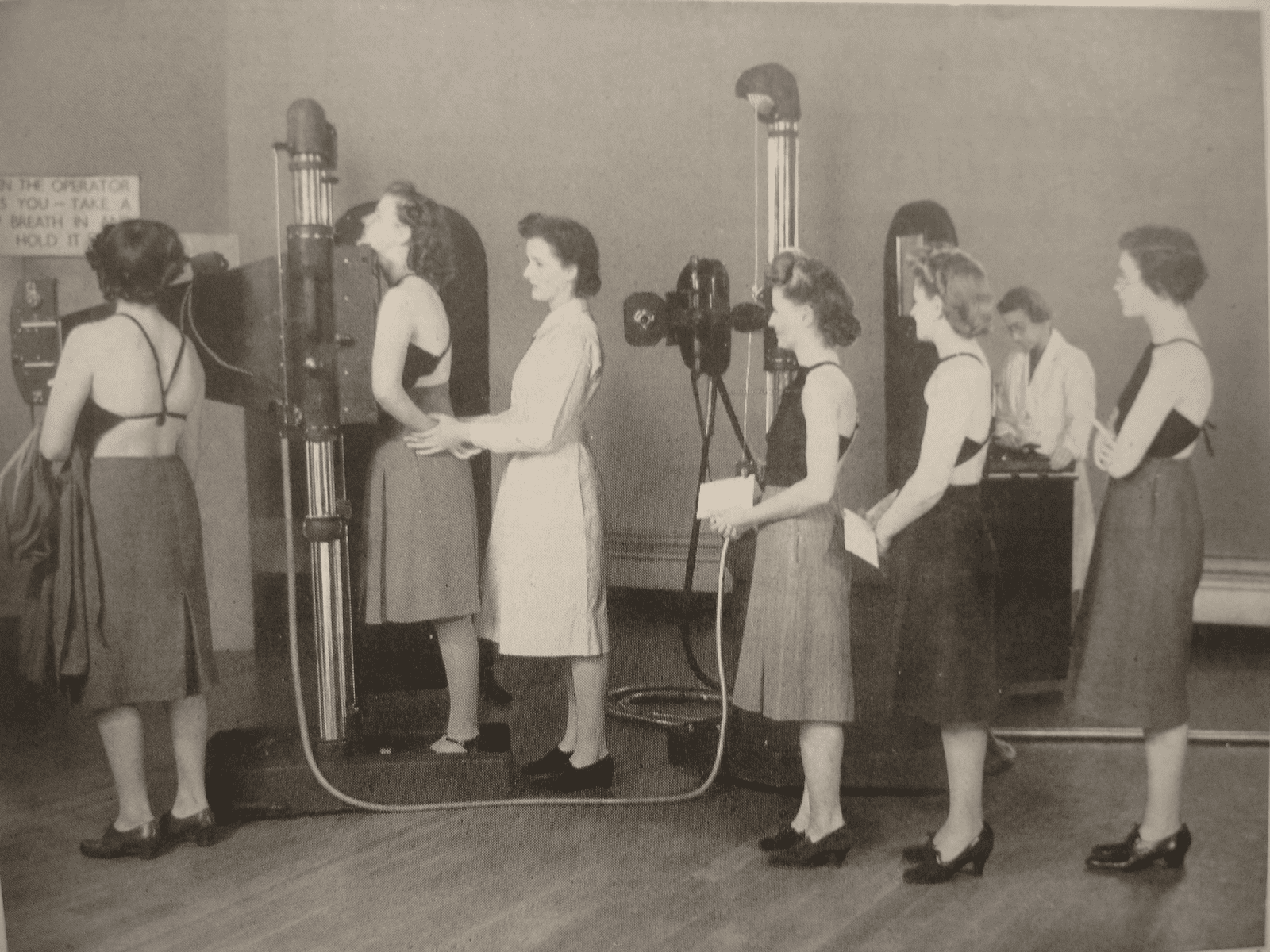

Liverpool didn’t rest on its 19th-century hygienic breakthroughs—the city kept pushing for progress. By the mid-20th century, it implemented what was a distant dream for many: mass screening for tuberculosis. Photographs from 1959 show mobile X-ray units traversing the city, allowing the disease to be detected in its early stages. This was a powerful demonstration of how preventive medicine could work effectively in practice.

The idea was simple: if a disease is seen, it can be stopped. But translating this logic into real action requires political will, and Liverpool had it. That’s why its example of X-ray screening began to be studied internationally. It was genuine ‘prevention in the field’, proving that hygiene is linked to social organisation, not just soap and water.

Decades later, Liverpool was once again at the forefront. In 2020, as COVID-19 began to spread across the country, it was here that the first UK-wide mass-testing programme was launched. The city took the initiative again: while many regions were still drawing up plans, Liverpool was already deploying mobile testing units, engaging volunteers, and analysing data in real-time.

Both stories—the X-rays and the COVID tests—share a common thread: the ability to act quickly, systematically, and with a focus on the common good. Liverpool was both an innovator and a practical testing ground for change.

A Living Legacy: How Liverpool Honours its Hygiene Pioneer

Today, Liverpool preserves the memory of its hygienic revolution. History breathes even in a pint glass: in the heart of the city stands Dr. Duncan’s pub, dedicated to the doctor who transformed ‘urban hygiene’ from theory into reality. Duncan’s name hasn’t faded, because the reasons he began his fight haven’t either. The film Hunting for History follows the steps of Dr. Sam Caslin of the University of Liverpool as she retraces her predecessor Duncan’s route: from the pub to the archives, and from memorial photographs to the city’s historic streets.

One of the most powerful visual reminders is Pembroke Place, one of the few surviving 19th-century developments. This is where immigrants arrived seeking opportunity, only to find themselves in dire straits: damp, airless rooms, unsanitary conditions, overcrowding, and no proper drainage.

Duncan didn’t just record these realities—he intervened decisively. He demanded that landlords repair their properties and exposed developers who ignored basic sanitary standards. For him, the urban environment was a factor that either supported life or destroyed it. The city archives, which Caslin explores in the film, show that it was through numerous reports, inspections, and sanitary directives that he achieved the changes that eventually became the norm.

Interestingly, Duncan wasn’t called a hero in his lifetime, yet after he died, life expectancy increased, mortality rates fell, and the system of public control over infrastructure expanded. He wasn’t curing one specific patient; he was saving the entire city—through hygiene, regulation, sober analytics, and sheer tenacity.

Liverpool was also home to Kitty Wilkinson—a woman with progressive views and a big heart. In the 19th century, she became known in Liverpool for her efforts to improve hygienic conditions among the poor and for the development of local wash houses and baths.