Is it possible to invent something that has already been “invented,” but to do it more profoundly, subtly, and with greater understanding? In Oliver Lodge’s case – yes. He experimented with electromagnetic waves even before the word “radio” became commonplace, created the first prototypes of wireless communication, and… lost the race for fame. Lodge is not often mentioned in school textbooks, but his contribution was so significant that without him, there would be no syntony, nor Marconi himself in the role we attribute to him. He was also a professor in Liverpool, an experimenter with light waves, a passionate advocate of spiritualism, and the author of dozens of scientific works. The website iliverpool.info tells how all this fit into one person.

The Lad from Stoke: How It All Began

Oliver Joseph Lodge was born in 1851 in Penkhull, near Stoke-on-Trent, into a factory owner’s family. Despite the family’s wealth, classical education wasn’t a priority – he was homeschooled until he was twenty. However, after enrolling at the University of London, he quickly caught up and became even more engrossed in physics, particularly new experiments in electricity and telegraphy.

Even then, he was interested in conceptual questions. How do waves transmit energy? Can they be “caught” at a distance? This was long before Hertz’s discoveries, which would be considered the start of the radio era. In his early works, Lodge deeply explored the properties of capacitors, induction, and wave resonance. And, interestingly, he went beyond research – trying to imagine future technology that would work without wires.

Next stop – Liverpool. It was there he would get a professorship, and also – a chance to put his ideas into practice.

The Liverpool Period: A Professor with a Vision for the Future

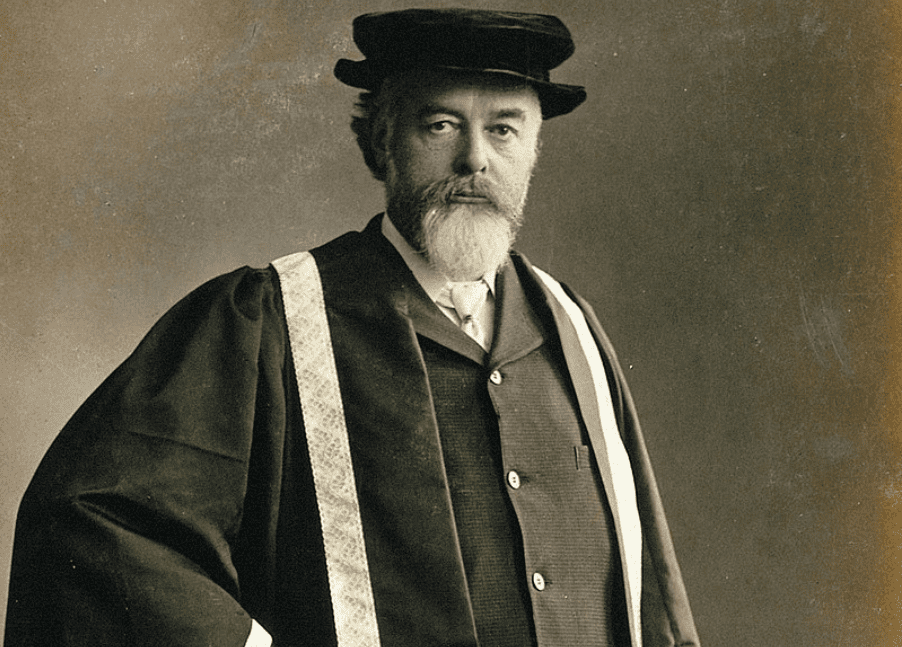

In 1881, Oliver Lodge became a Professor of Physics at University College Liverpool – a place that was just beginning to establish its reputation in academic circles. But for Lodge, it was an ideal platform: free from dogma, open to new ideas, with a strong industrial base around it. His courses on electricity, magnetism, and experimental physics quickly gained popularity among students, engineers, and entrepreneurs.

However, Oliver was most remembered for his ability to think outside the box. In 1894, almost immediately after the publication of Heinrich Hertz’s works, Lodge publicly demonstrated wireless signal transmission using electromagnetic waves. And although Hertz himself didn’t believe his discovery had practical application, Lodge was convinced otherwise: transmitting signals over a distance was entirely feasible. This was the idea he tried to prove in Liverpool lecture halls and during numerous public lectures, including at the famous Royal Institution.

His laboratory became the site of the first experiments with “syntonic” transmission – that is, tuning the transmitter and receiver to the same frequency. This discovery would later form the basis of all modern wireless technology – from radio to Wi-Fi. But back then, it seemed almost mystical. In Liverpool, Lodge felt right at home: a city that connected the world via ships and telegraphs naturally became the cradle of yet another type of communication – ethereal.

To the Airwaves! Radio Waves, Coherers, and Syntony

The late 19th century was a time of great physical discoveries… and great misunderstandings. What we call radio today didn’t yet have a name, but it had dozens of different interpretations. It was during this period that Oliver Lodge focused on learning how to control electromagnetic waves once they were captured. This was already a premonition of a new era of wireless communication.

What Exactly He Invented

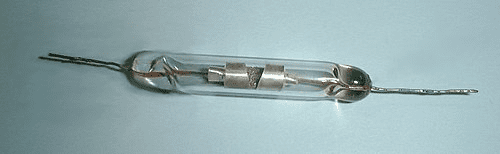

Lodge’s main technical innovation was an improved coherer – a device capable of reacting to the passage of radio waves. He didn’t invent the idea, but it was Lodge who made the coherer practical: he added a special mechanism that automatically “reset” the device after each signal. This allowed messages to be registered sequentially and reliably – like in a telegraph, but without a wire.

Even more important was his understanding of the principle of resonance: the transmitter and receiver must operate on the same frequency to avoid interference. Lodge called this “syntonic communication,” and in 1898, he received a patent for it. The idea was so revolutionary that in 1912, Marconi’s company was forced to buy it to avoid a lawsuit. The very Marconi, who is today considered the father of radio, initially ignored this development, but later it was precisely this that enabled the improvement of transmitters.

Disputed Authorship of the Invention

Lodge had a complex relationship with Marconi. At first – mutual interest and exchange of ideas, then – competition, which quickly escalated into a patent war. Although both scientists worked independently, Lodge’s publications preceded Marconi’s first major demonstrations. However, it was the Italian who skilfully seized the moment: he was younger, more ambitious, and had stronger business connections.

Legal disputes dragged on for years. Lodge repeatedly insisted that his patents had been used without permission, and eventually achieved partial recognition: Marconi’s company acquired the rights to “syntonic” communication. But in the popular imagination, the winner remained the one who managed to transmit the signal across the Atlantic – perhaps not first, but loudly.

So, who really invented radio? The truth, as often happens, is more complex than the myth. Without Lodge, radio would not work as we know it. But without Marconi, perhaps it would not have existed in a commercial sense.

From Scientist to Mystic: A Turn Towards Spiritualism

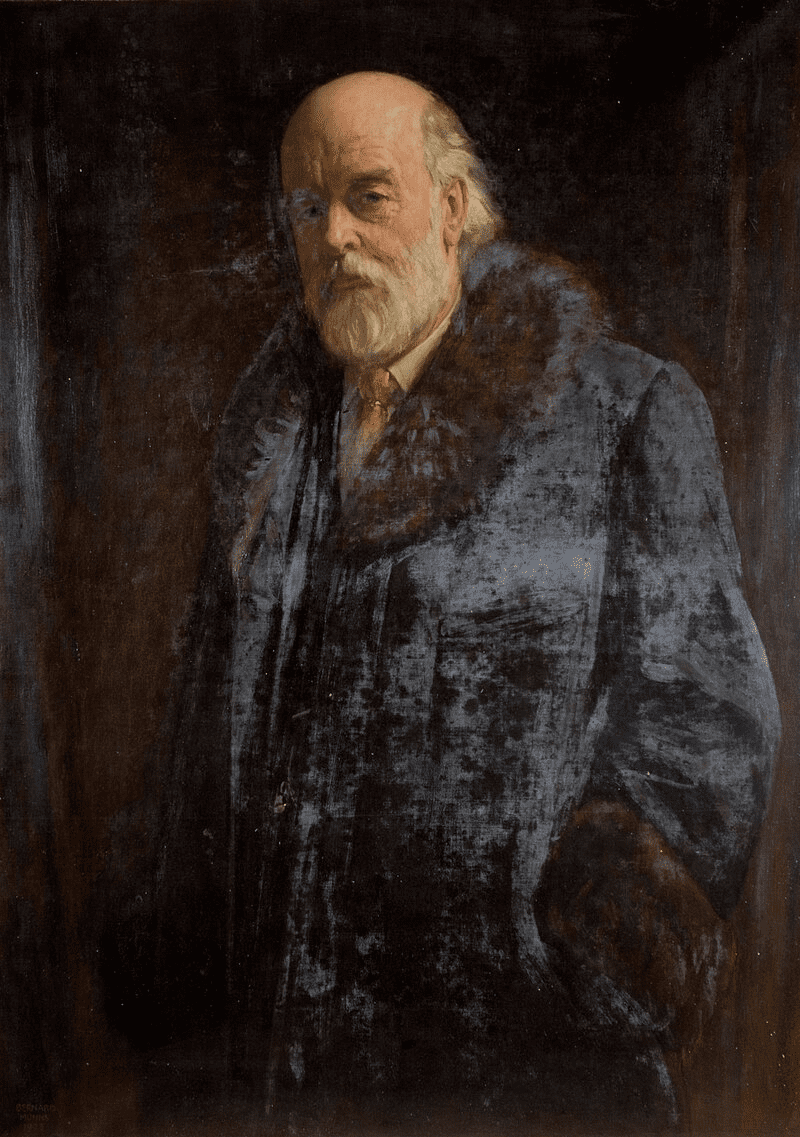

Oliver Lodge’s scientific career could have ended conventionally: professorial retirement, honorary awards, mentions in textbooks. But life had a different turn in store for him. In 1915, during the First World War, his son Raymond died – and this was a painful blow that forever changed both Lodge’s worldview and his scientific interests.

Already in his mature age, the physicist, known for his logical thinking and precision, turned to what most of his colleagues considered fraud – spiritualism. He began to study messages from mediums, recorded “communication sessions” with his deceased son, and tried to derive some regularity from them.

Seeking Answers After the Loss of His Son

Raymond Lodge died in battle at Ypres, and just a few months after the funeral, Oliver began to receive, as he claimed, contacts with him through mediums. Lodge was so impressed by the “accuracy” of the received messages that he published the book Raymond or Life and Death (1916), where he detailed these attempts at communication with the other side.

Lodge truly believed he was doing the right thing. He even publicly stated that science and religion do not contradict each other, and that the spiritual world is real, only yet unexplored. His lectures on the immortality of the soul, life after death, and spiritual energy caused a sensation, and at the same time – ridicule.

A Rift in the Scientific Community

Of course, such a position did not go without consequences. Many colleagues began to distance themselves from Lodge. His authority as a physicist gradually faded – not because of the weakness of his scientific works, but because he had seemingly “betrayed the method.”

Lodge, however, did not consider it a betrayal. He remained convinced until the end of his life that true science is the search for answers to all questions, even if they lie beyond the microscope or a formula. For him, spirit and matter were not in opposition, but rather existed as two manifestations of the same reality.

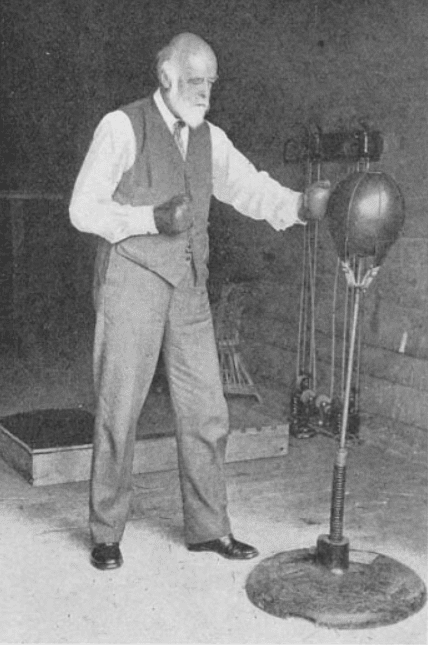

An Underestimated Legacy

Despite the fact that many of our hero’s ideas became the basis of modern communication, Oliver Lodge’s name cannot be called popular. He didn’t have a resounding victory in the style of Marconi, but he had a depth of understanding – it was he who helped “tune” the world to the frequency of the future. Like another underestimated engineer from Liverpool, Henry Booth (author of revolutionary solutions in transport infrastructure), Lodge remained in the shadows, but that didn’t stop him from being a brilliant innovator.